A (human) index that likes to code

Also drinks way too much coffee ![]()

Developing GitLab CI pipelines locally

Published Aug 29, 2023 06:55

Hey there, good morning. Sit yourself down, and enjoy some ![]() .

.

Recently, I’ve worked heavily on GitLab CI/CD pipelines. In my line of work, these pipelines must incorporate security requirements, such as Static Application Security Testing (SAST), Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST), Code Scanning, Dependency Scanning, and so on. Furthermore, the pipelines themselves should be templated to support several deployment variants, e.g. managed cloud services, and Kubernetes.

As with all things, if you’ve dedicated 60% of your time on something for 3 months, you’re sure to develop a love-hate relationship with that particular thing. For example, here is one gripe I have for GitLab CI/CD:

According to Variable Precedence, Project Variables have higher precedence compared to

.gitlab-ci.ymlvariables. Hence, why in the world are.gitlab-ci.ymlvariables passed down to child pipelines spawned viatrigger? That overrides the settings I’ve set in Project Variables, and it just doesn’t make any sense.

Moreover, there are so many issues open on GitLab’s own repository regarding CI that I sometimes find myself wondering if the tool is actually production-ready. Luckily (for you), this blog post is not about all the 789 problems I have with GitLab CI; instead, it is about the biggest painpoint I had when developing pipelines: not being able to develop them locally.

Why is this a problem?

Typically, if you were to develop a pipeline, you’d really only know if it worked when you push the commit to a branch somewhere. On a good day, the pipeline would fail because of some misconfigured variables; for example, wrong SonarQube credentials. In that scenario, you’d just have to modify the CI/CD variable from your settings, and invoke the reincarnation of our lord and savior: the retry button.

The Retry Button

What if the problem arises from your script? Unfortunately, this would mean you’d have to vim into

your YAML config, change the offending script, create a commit, push, and wait for the entire

pipeline to go through before you’d get feedback on whether your job is successful.

As a pipeline author, my job is to architect pipelines that will fail quickly so that developers get feedback as soon as something is wrong. Why, as the pipeline author, do I have to wait for an entire pipeline to figure out if I’ve fixed a job 4 stages later?

Being unable to test a pipeline locally would also pollute the commit logs with unnecessary commits; of course, I can simply

squash them prior to merging the gitlab-ci.yml file into the default branch, but I still find it

clunky and inelegant. The worst I’ve done is pushing 70 CI-related commits in a single afternoon,

debugging GitLab CI services. For some reason, services networking wasn’t functioning properly for

an in-runner DAST scan.

By the way,

$CI_DEBUG_SERVICESis not an omnipotent flag that forces applications to produce logs; in some Kubernetes configurations, services simply won’t output logs.

In an ideal world, I’d be able to run the entire pipeline locally. Hence, I looked online and found firecow/gitlab-ci-local.

This tool makes use of docker to emulate the functionality of GitLab CI/CD, and even has

services support. The feature parity is the most accurate I’ve seen; in fact, I’ve contributed PR #905

which pushes the tool closer to feature parity with actual CI/CD pipelines on GitLab.

The remainder of this blog post will walk through the typical workflow I follow when developing

pipelines, which is not a comprehensive look into the full features provided by

gitlab-ci-local. The focus here is feature parity, meaning to change as little as possible in

.gitlab-ci.yml to get a pipeline working on both the runner, and locally on your computer.

Typical Usage

There are instructions for setting up the tool on various platforms in the tool’s README.md, so get Docker and the tool installed before continuing.

Let’s suppose we have a simple .gitlab-ci.yml file, like this:

image: debian:latest

stages:

- some-stage

some-job:

stage: some-stage

script:

- echo "Hello, world"

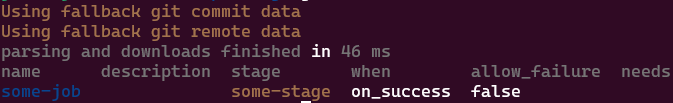

If you run this with gitlab-ci-local --list, you should see some-job:

some-job is listed

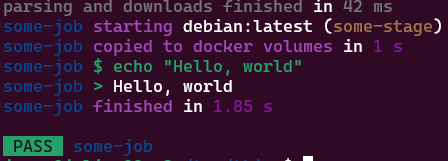

Let’s quickly run it: gitlab-ci-local some-job:

some-job output works locally

This allows us to run fairly simple jobs that takes in no variables. What if we want some variables?

Let’s update the .gitlab-ci.yml file:

image: debian:latest

stages:

- some-stage

some-job:

stage: some-stage

script:

- echo "$SOME_TEXT"

If we suppose the variable will be set within GitLab’s CI/CD settings, then surely we need to have our

“local” version of those settings; this is achieved via the .gitlab-ci-local-variables.yml file.

Let’s create that file, and define SOME_TEXT:

SOME_TEXT: "hello from the other side!"

Great, let’s make it so that our job creates some sort of artifact. This pattern is commonly found in build jobs:

# ... just change some-job

some-job:

stage: some-stage

script:

- echo $SOME_TEXT > some_output

artifacts:

paths:

- some_output

If you were to execute gitlab-ci-local some-job now, you should observe that some_output appears

within your directory. By default, the tool will copy the artifacts to the root of the repository,

for your inspection. Of course, you can turn this off by running: gitlab-ci-local

--artifacts-to-source=false some-job.

Let’s suppose we write another job in the same stage, that depends on that above dependency:

# append this job into your .gitlab-ci.yml file

another-job:

stage: some-stage

script:

- echo "The file outputs"

- cat some_output

needs:

- some-job

dependencies:

- some-job

If we now run gitlab-ci-local another-job, we should see that this job is able to get the

artifacts from the dependent job. Caches also work the same way.

You’d have noticed that I specified the job to run: gitlab-ci-local another-job, and

noted that artifacts and caches are propagated correctly. This saves lots of development time - you don’t have to run

all of the stages prior to the current job to check if your job works. This, to me, is a massive

improvement from the original cycle of iteration, which required me to commit every change, waiting

for all pre-requisites stages to run, only to be met with yet another error message to fix.

The whole pipeline can now be run with just simply gitlab-ci-local. If you just want to run a

single stage, then run gitlab-ci-local --stage some-stage.

Registries

Typically, upon a successful build, we would want to upload the artifacts to some registry. For example, if I were to build a container, it is likely that I want to push to some sort of Docker registry.

GitLab offers a bunch of registries, including a Container Registry; you can read more about the supported registry here.

Note: As a GitLab user, you can authenticate to the Container Registry using your username, and a Personal Access Token via

docker login. The registry URL will typically be:registry.<gitlab url>.com, where<gitlab url>is the instance URL. You can then use images from the Container Registry, like so:images: registry.<gitlab url>.com/some/project/path/image:latestBy default, GitLab runners will already be authenticated to the registry, so there is no additional step to authenticate your jobs.

Another Note: To push to the container registry, you need to define the following variables within your

.gitlab-ci-local-variables.yml:CI_REGISTRY_USER: some-username CI_REGISTRY_PASSWORD: some-password CI_REGISTRY_IMAGE: <registry URL>/<namespace>/<project>

Let’s say we’re on an esoteric project that doesn’t really use any of the above registries; so we’d choose to use the Generic Package Registry.

On GitLab runners, a token known as $CI_JOB_TOKEN will be populated automatically, allowing the CI

job to authenticate to most GitLab services without any additional configuration from the job

runner. This also bypasses issues related to secrets rotation, which is a huge boon overall for

everyone involved.

However, $CI_JOB_TOKEN will not be populated automatically when running gitlab-ci-local, because

obviously, there just isn’t a valid job token to use. Hence, the obvious solution is to use a

Project Access

Token,

and then change our .gitlab-ci-local-variables.yml to reflect the token:

# ...whatever variables before

CI_JOB_TOKEN: <project access token here>

However, upon closer inspection from the GitLab

documentation,

we observe that the curl command has an issue:

curl --header "PRIVATE-TOKEN: <project_access_token>" \

--upload-file path/to/file.txt \

"https://gitlab.example.com/api/v4/projects/24/packages/generic/my_package/0.0.1/file.txt?select=package_file"

Here’s the catch: $CI_JOB_TOKEN that is populated by the runner has the type of BOT-TOKEN, which

means that the correct flag to use in the job would be --header "JOB-TOKEN: $CI_JOB_TOKEN".

However, the Project Access Token we’ve generated earlier requires the flag to be: --header

"PRIVATE-TOKEN: $CI_JOB_TOKEN to run locally.

Remember the motto we’ve established earlier: feature parity with GitLab runner. With the motto in

mind, we simply change the flag to be: --header "$TOKEN_TYPE: $CI_JOB_TOKEN". According to

variable precedence, since our .gitlab-ci-variables.yml is considered to be a part of “Project

Variables”, it has a higher precedence compared to job variables. So, all we need to do now is to set the job

variable to TOKEN_TYPE: JOB-TOKEN, and set TOKEN_TYPE: PRIVATE-TOKEN within

gitlab-ci-variables.yml.

Hence, the final curl command that should be used is:

curl --header "$TOKEN_TYPE: $CI_JOB_TOKEN" --upload-file some_output "https://gitlab.example.com/api/v4/projects/24/packages/generic/my_package/0.0.1/some_output?select=package_file"

So, we create a job within our .gitlab-ci.yml, like this:

# append

upload-job:

image: curlimages/curl

stage: some-stage

needs:

- some-job

dependencies:

- some-job

variables:

TOKEN_TYPE: JOB-TOKEN

script:

- curl --header "$TOKEN_TYPE: $CI_JOB_TOKEN" --upload-file some_output "https://gitlab.example.com/api/v4/projects/24/packages/generic/my_package/0.0.1/some_output?select=package_file"

And then amend our .gitlab-ci-local-variables.yml like so:

# ...whatever variables before

CI_JOB_TOKEN: <project access token here>

TOKEN_TYPE: PRIVATE-TOKEN

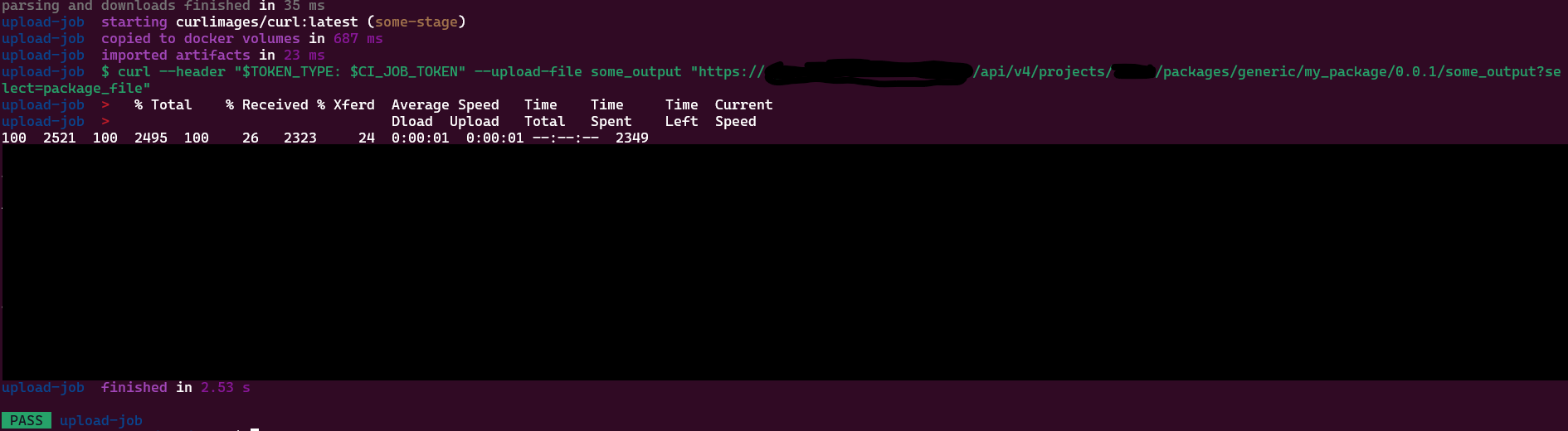

Running gitlab-ci-local upload-file should then yield a successful result:

A successful publish

A file output

Needless to say, this .gitlab-ci.yml also works when pushed to GitLab.

Including

In large enough enterprises, you may encounter the need to include other templates, something like

this:

# appears at the top of the gitlab-ci.yml file

include:

- project: "some-template-project"

ref: "some-tag"

file:

- BUILD.gitlab-ci.yml

- COPY.gitlab-ci.yml

- TEST.gitlab-ci.yml

As long as you have access to git clone the current repository, the include will work

transparently with the local tool.

The

gitlab-ci-localtool looks through your Git remote list, picks the first one, and attempts to fetch the referenced files.

This is useful because you can now do gitlab-ci-local --preview | less, which will render all of

the included files into one gigantic file. If you have multiple layers of include, i.e. the

included references also includes other references, they will all be flattened and displayed.

This makes debugging templates much easier.

Another file

In some pipeline architectures, child pipelines are heavily relied upon. In such configurations, you may have two pipeline files, maybe something like:

-

.gitlab-ci.ymlfor common CI work, -

DEPLOYMENT.gitlab-ci.ymlfor project-specific deployment

Where you have a .gitlab-ci.yml job that looks something like this:

spawn-child-pipeline:

stage: some-stage

trigger:

include: DEPLOYMENT.gitlab-ci.yml

GitLab’s own pipeline editor doesn’t support multiple files; hence, you won’t have the nice features to validate rules, checking conditions, etc.

However, that isn’t an issue with gitlab-ci-local; simply add the --file

DEPLOYMENT.gitlab-ci.yml file during development. All the suffixes used thus far, such as --list

and --preview work as expected.

Unfortunately, it seems like trigger is currently not supported by the local tool; you can only

perform a “close” imitation by running this command:

gitlab-ci-local --file "DEPLOYMENT.gitlab-ci.yml" --variable CI_PIPELINE_SOURCE=parent_pipeline

Pushing to registries (without GitLab)

Sometimes, when testing locally, you may not want to pollute the GitLab registry with unnecessary container images. In scenarios like this, it might be useful to create your own local registry for testing. Here’s a useful script to create 3 registries at once:

#!/bin/bash

if [[ "$1" == "" ]]; then

docker run -d -p 5000:5000 --name registry -v "$(pwd)"/auth:/auth -v "$(pwd)"/certs:/certs -e "REGISTRY_AUTH=htpasswd" -e "REGISTRY_AUTH_HTPASSWD_REALM=Registry Realm" -e REGISTRY_AUTH_HTPASSWD_PATH=/auth/htpasswd registry:2

docker run -d -p 5001:5000 --name registry2 -v "$(pwd)"/auth:/auth -v "$(pwd)"/certs:/certs -e "REGISTRY_AUTH=htpasswd" -e "REGISTRY_AUTH_HTPASSWD_REALM=Registry Realm" -e REGISTRY_AUTH_HTPASSWD_PATH=/auth/htpasswd registry:2

docker run -d -p 5002:5000 --name registry3 -v "$(pwd)"/auth:/auth -v "$(pwd)"/certs:/certs -e "REGISTRY_AUTH=htpasswd" -e "REGISTRY_AUTH_HTPASSWD_REALM=Registry Realm" -e REGISTRY_AUTH_HTPASSWD_PATH=/auth/htpasswd registry:2

fi

if [[ "$1" == "stop" ]]; then

docker stop registry

docker stop registry2

docker stop registry3

docker rm registry

docker rm registry2

docker rm registry3

fi

You can then hijack the $CI_REGISTRY_* variables via .gitlab-ci-local-variables.yml to point to your local registry:

CI_REGISTRY_USER: some-username

CI_REGISTRY_PASSWORD: some-password

CI_REGISTRY_IMAGE: 172.17.0.2:5000 # use your docker IP here, using docker inspect

To create a user, do the following:

mkdir -p auth \

docker run --entrypoint htpasswd httpd:2 -Bbn testuser testpassword >> auth/htpasswd \

docker run --entrypoint htpasswd httpd:2 -Bbn AWS testpassword >> auth/htpasswd

To list the images in the registry:

curl -X GET -u testuser:testpassword http://localhost:5000/v2/_catalog

The above spawns registries without TLS verification. If you’re using skopeo, you may have to set

--src-tls-verify=false and --dest-tls-verify=false in your job scripts, via something akin to $ADDITIONAL_OPTS.

Conclusion

Generally speaking, developing pipelines can be fairly painful; however, towards DevOps and

automating the pain of deploying applications, it is a necessary sacrifice. By using supporting

tools such as gitlab-ci-local, engineers can quickly iterate through pipeline development.

Hopefully, both the tool and this blog post has proved useful for any pipeline work you’ll be doing.

Happy Coding,

CodingIndex