A (human) index that likes to code

Also drinks way too much coffee ![]()

TOTP from scratch

Published Mar 07, 2021 10:54

“How do One-Time Passwords (OTP) work?” I asked myself, as I fiddled with my digital banking token to check my non-existent wealth online.

Is there some kind of magic communicating protocol and hardware that I didn’t know of? Perhaps GSM is being used in these banking tokens, or mobile data is being used in my Google Authenticator app?

Well, of course not. Firstly, hardware tokens need to be low-power and durable; radio communication isn’t exactly the best thing to fit those criteria. Secondly, it would be ridiculous to spend mobile data for a 6 to 8 digit pin. Some quick preliminary research shows that OTPs are generated offline, via a pre-shared key known to both the verifier (i.e. the entity that needs to know it’s you) and the generator (i.e. you).

Naturally, the next question to ask is: “How?”

And, as commonsensical as dunking a donut into beer, I decided to understand and implement Time-based OTP (TOTP) and its components from scratch. The aftermath of this disaster can be found on my GitHub repository, which comes with GitHub Actions powered tests because I like torturing myself.

Table Of Contents

Hashes

TOTP, or lesser known as RFC 6238, is a simple algorithm built on the already existing counter-based OTP algorithm, Hash-Message-Authenticator-Code-based OTP (HOTP). As the name suggests, HOTP uses hashes; in RFC 4226, the preferred hashes belong to the SHA family, specifically SHA1.

If you’ve dabbled with hashes, you would know that alongside MD5, SHA-1 is known to be “broken”; two PDFs of differing content has colliding SHA-1 functions according to an article on ComputerWorld. An alternative interpretation is that SHA-1 is no longer cryptographically safe. However, most of the internet still uses SHA-1 to generate OTPs; while practically infeasible to impersonate, it is nevertheless still a concern for the paranoid.

To ease my mind a little, I also decided to implement SHA-256 and SHA-512 as “drop-in” replacements for SHA-1 when it comes to OTP generation. Hence, this blog post will describe the implementation of SHA-1, SHA-256, and SHA-512.

SHA-1

Implementing SHA-1 was similar to implementing MD5; although, I ran into some problems specific to the width of uint_fast*_t types. In a nutshell, don’t use those types - they likely have larger widths which may mess up the hash on a careless programmer’s code (i.e. me).

Before we begin, let’s define a few things:

-

WORDis a 32-bit string (== 4 bytes) that can be represented as a sequence of 8 hex digits; in C, this isuint32_t, - Everything in SHA-1 is processed in blocks of 512-bits, which is 16 words or 64 bytes,

- Everything in the SHA family should be expressed in Big Endian byte order; furthermore, platform-agnostic endianness should be enforced.

In RFC 3174 section 5, some functions are defined for use by SHA-1. In C, they are implemented like so:

SHA1_WORD sha1_f(uint8_t t, SHA1_WORD B, SHA1_WORD C, SHA1_WORD D) {

if (t <= 19) {

return (B & C) | ((~B) & D);

} else if (t <= 39) {

return B ^ C ^ D;

} else if (t <= 59) {

return (B & C) | (B & D) | (C & D);

} else if (t <= 79) {

return B ^ C ^ D;

}

exit(1); // impossible case

}

SHA1_WORD sha1_K(uint8_t t) {

if (t <= 19) {

return 0x5A827999;

} else if (t <= 39) {

return 0x6ED9EBA1;

} else if (t <= 59) {

return 0x8F1BBCDC;

} else {

return 0xCA62C1D6;

}

exit(2); // impossible case

}

The hex digits are copied from the RFC, although it is likely that these are fractional components of the square root of some prime number. Another commonly used function, Shift & Rotate Left should also be defined:

SHA1_WORD sha1_Sn(SHA1_WORD X, uint8_t n) {

return (X << n) | (X >> 32 - n);

}

SHA-1 uses a form of metadata encoding to pad blocks; all blocks must be padded with this metadata no matter its size. Should the addition of the padding exceed the block size, a new block is created. Padding in SHA-1 follows these rules:

- Append a bit ‘1’ to the end of the string;

- Append zeros until the following equation is satisfied:

(bitLengthOfMessage + 1 + X) % 512 == 448, wherebitLengthOfMessageis the bit length of the original message, andXis the number of zeros to append at the end of the message.

The following code pads the message, assuming that all the data are aligned nicely to their bytes:

uint8_t* sha1_pad(const void* msg, size_t size, size_t* newSize) {

if (!msg) {

return 0;

}

size_t toPad = 64 - (size % 64);

if (toPad < 9) { // spillover

toPad += 64;

}

uint8_t* newArr = (uint8_t*) malloc(size + toPad);

memcpy(newArr, msg, size);

newArr[size] = 0x80;

memset(newArr + size + 1, 0x00, toPad - 8); // -8 for 2 words at the back

/*

* This code relies too much on the endianess of the system, so we won't be using it

* uint64_t* ref = (uint64_t*) (newArr + size + toPad - 8);

* ref = size * 8;

*/

const uint64_t sizeInBits = size * 8;

const uint8_t ptr = size + toPad - 8;

newArr[ptr] = sizeInBits >> 56;

newArr[ptr + 1] = sizeInBits >> 48;

newArr[ptr + 2] = sizeInBits >> 40;

newArr[ptr + 3] = sizeInBits >> 32;

newArr[ptr + 4] = sizeInBits >> 24;

newArr[ptr + 5] = sizeInBits >> 16;

newArr[ptr + 6] = sizeInBits >> 8;

newArr[ptr + 7] = sizeInBits;

if (newSize) {

*newSize = size + toPad;

}

return newArr;

}

Notice that towards the end of the function, a platform-agnostic way of maintaining the big-endian byte order is used.

With all of the pre-requisites in place, the main hashing process can now be done. RFC 3174 gave two different methods to accomplish this; both are essentially the same, except that the second method uses an intelligent way to access data if the underlying message is stored as an array of WORDs. For the purpose of clarity, only the first method will be explained in this blog post. The SHA-1 algorithm does the following:

- Define magic numbers

h0toh4with values stated in RFC 3174; - Pad the message using

sha1_pad; - Split the message into blocks of 512-bits;

- Create a working buffer of 80 WORDS;

- Copy the contents of the 64-byte block into the working buffer (i.e. copy 16 WORDS), using a platform-agnostic way to maintain Big Endianness;

- Generate the values of the remaining words with an algorithm specified in RFC 3174;

- Calculate the intermediary hash;

- Copy the digest back into

h0toh4. - When all blocks are processed, return

h0toh4as an array of bytes, maintaining the Big Endian byte order.

Normally, hashing algorithms are implemented with streams in mind, meaning that blocks of data are fed to the algorithm before being finalized into a hash. Given that TOTP would have all the data it needs on-demand, I figured it was not necessary to worry about streaming, instead building a single function to hash the whole message.

uint8_t* method_one(const void* msg, size_t size) {

SHA1_WORD h0 = 0x67452301;

SHA1_WORD h1 = 0xefcdab89;

SHA1_WORD h2 = 0x98badcfe;

SHA1_WORD h3 = 0x10325476;

SHA1_WORD h4 = 0xc3d2e1f0;

h0, h1, h3, and h4 are magic initial numbers used by the algorithm; they will be changed later on as the hash digests the data. I am not a security expert, but I gather that these numbers could be anything - perhaps you can make your own variant of SHA-1 just by changing these numbers.

Pad the message carefully.

size_t messageSize = 0;

uint8_t* message = sha1_pad(msg, size, &messageSize);

Processing the message block by block, we define a temporary buffer, W, with the size of 80 WORDS to store data that would later become a hash digest. Then, the first 64 bytes (i.e. 16 WORDS) would be copied into W, with the endian maintained through a platform-agnostic method.

for (int i = 0; i < messageSize; i += 64) {

int t = 0;

uint8_t* block = message + i;

SHA1_WORD W[80];

for (t = 0; t < 16; t++) {

W[t] = block[t * 4] << 24;

W[t] |= block[t * 4 + 1] << 16;

W[t] |= block[t * 4 + 2] << 8;

W[t] |= block[t * 4 + 3];

}

Fill the rest of W with a method specified in RFC 3174. This step, is the only line that differs between method_one and method_two.

for (t = 16; t < 80; t++) {

W[t] = sha1_Sn(W[t - 3] ^ W[t - 8] ^ W[t - 14] ^ W[t - 16], 1);

}

With all the data filled into W, compute the hash by digesting every WORD in W with the above algorithm. This part will be referred to as “the main hashing process” for the remainder of this blog post.

SHA1_WORD A = h0;

SHA1_WORD B = h1;

SHA1_WORD C = h2;

SHA1_WORD D = h3;

SHA1_WORD E = h4;

SHA1_WORD TEMP = 0;

for (t = 0; t < 80; t++) {

TEMP = sha1_Sn(A, 5) + sha1_f(t, B, C, D) + E + W[t] + sha1_K(t);

E = D;

D = C;

C = sha1_Sn(B, 30);

B = A;

A = TEMP;

}

Add the intermediary variables back into h0 to h4.

h0 += A;

h1 += B;

h2 += C;

h3 += D;

h4 += E;

}

SHA-1 returns a 160-bit string (i.e. 20 bytes) as a hash result. After taking care of memory management, copy the data from h0 to h4 in a platform-agnostic way to preserve Big Endianness. Return the result, and call it a day.

free(message);

uint8_t* retVal = (uint8_t*) malloc(20);

SHA1_WORD* retValView = (SHA1_WORD*) retVal;

retValView[0] = h0;

retValView[1] = h1;

retValView[2] = h2;

retValView[3] = h3;

retValView[4] = h4;

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

SHA1_WORD temp = retValView[i];

retVal[i * 4] = temp >> 24;

retVal[i * 4 + 1] = temp >> 16;

retVal[i * 4 + 2] = temp >> 8;

retVal[i * 4 + 3] = temp;

}

return retVal;

The full code to compute SHA-1 can be found in my GitHub repository; the file is project-independent, so you can drop it into your codebase. Do note that nothing within the repository is production-ready, since roll-your-own-crypto is a bad idea. Use libraries such as openssl or libressl.

In theory, SHA-1 is all you need for modern TOTP, especially with the use of Google Authenticator, since, at the time of writing, the algorithm parameter that specifies the hashing algorithm is ignored by Google Authenticator.

SHA-256 (Optional)

SHA-256 and SHA-1 defers by the magic values used in K, the binary operations used for the hash, and the main hashing process. Furthermore, SHA-256 has a 256-bit output (32 bytes). The padding method is still the same as defined in SHA-1.

K, the magic values, is defined with an array tackling 64 WORDS in SHA-256 rather than 4 magic values over 80 WORDS in SHA-1:

const SHA2_WORD SHA2_K[] = {

0x428a2f98, 0x71374491, 0xb5c0fbcf, 0xe9b5dba5,

0x3956c25b, 0x59f111f1, 0x923f82a4, 0xab1c5ed5,

0xd807aa98, 0x12835b01, 0x243185be, 0x550c7dc3,

0x72be5d74, 0x80deb1fe, 0x9bdc06a7, 0xc19bf174,

0xe49b69c1, 0xefbe4786, 0x0fc19dc6, 0x240ca1cc,

0x2de92c6f, 0x4a7484aa, 0x5cb0a9dc, 0x76f988da,

0x983e5152, 0xa831c66d, 0xb00327c8, 0xbf597fc7,

0xc6e00bf3, 0xd5a79147, 0x06ca6351, 0x14292967,

0x27b70a85, 0x2e1b2138, 0x4d2c6dfc, 0x53380d13,

0x650a7354, 0x766a0abb, 0x81c2c92e, 0x92722c85,

0xa2bfe8a1, 0xa81a664b, 0xc24b8b70, 0xc76c51a3,

0xd192e819, 0xd6990624, 0xf40e3585, 0x106aa070,

0x19a4c116, 0x1e376c08, 0x2748774c, 0x34b0bcb5,

0x391c0cb3, 0x4ed8aa4a, 0x5b9cca4f, 0x682e6ff3,

0x748f82ee, 0x78a5636f, 0x84c87814, 0x8cc70208,

0x90befffa, 0xa4506ceb, 0xbef9a3f7, 0xc67178f2

};

According to RFC 6234, these constants represent “the first 32 bits of the fractional parts of the cube roots of the first sixty-four prime numbers”.

The binary operations are defined with the following code:

SHA2_WORD sha2_ROTR(SHA2_WORD X, uint8_t n) {

return (X >> n) | (X << (32 - n));

}

SHA2_WORD sha2_CH(SHA2_WORD X, SHA2_WORD Y, SHA2_WORD Z) {

return (X & Y) ^ ((~X) & Z);

}

SHA2_WORD sha2_MAJ(SHA2_WORD X, SHA2_WORD Y, SHA2_WORD Z) {

return (X & Y) ^ (X & Z) ^ (Y & Z);

}

SHA2_WORD sha2_BSIG0(SHA2_WORD X) {

return sha2_ROTR(X, 2) ^ sha2_ROTR(X, 13) ^ sha2_ROTR(X, 22);

}

SHA2_WORD sha2_BSIG1(SHA2_WORD X) {

return sha2_ROTR(X, 6) ^ sha2_ROTR(X, 11) ^ sha2_ROTR(X, 25);

}

SHA2_WORD sha2_SSIG0(SHA2_WORD X) {

return sha2_ROTR(X, 7) ^ sha2_ROTR(X, 18) ^ (X >> 3);

}

SHA2_WORD sha2_SSIG1(SHA2_WORD X) {

return sha2_ROTR(X, 17) ^ sha2_ROTR(X, 19) ^ (X >> 10);

}

ROTR stands for right shift. I have no idea what the other abbreviations mean.

Padding in SHA-256 is the same as that in SHA-1:

uint8_t* sha2_pad(const void* msg, size_t size, size_t* newSize) {

if (!msg) {

return 0;

}

size_t toPad = 64 - (size % 64);

if (toPad < 9) {

toPad += 64;

}

uint8_t* newArr = (uint8_t*) malloc(size + toPad);

memcpy(newArr, msg, size);

newArr[size] = 0x80;

memset(newArr + size + 1, 0x00, toPad - 8);

const uint64_t sizeInBits = size * 8;

const uint8_t ptr = size + toPad - 8;

newArr[ptr] = sizeInBits >> 56;

newArr[ptr + 1] = sizeInBits >> 48;

newArr[ptr + 2] = sizeInBits >> 40;

newArr[ptr + 3] = sizeInBits >> 32;

newArr[ptr + 4] = sizeInBits >> 24;

newArr[ptr + 5] = sizeInBits >> 16;

newArr[ptr + 6] = sizeInBits >> 8;

newArr[ptr + 7] = sizeInBits;

if (newSize) {

*newSize = size + toPad;

}

return newArr;

}

The pre-requisites are done. For the SHA-256, 8 WORDS (256-bits) will be returned as the final hash; hence, 8 variables will be used to represent the working variables to compute the hash:

uint8_t* sha256(const void* msg, size_t size) {

SHA2_WORD h0 = 0x6a09e667;

SHA2_WORD h1 = 0xbb67ae85;

SHA2_WORD h2 = 0x3c6ef372;

SHA2_WORD h3 = 0xa54ff53a;

SHA2_WORD h4 = 0x510e527f;

SHA2_WORD h5 = 0x9b05688c;

SHA2_WORD h6 = 0x1f83d9ab;

SHA2_WORD h7 = 0x5be0cd19;

Unlike SHA-1, these numbers aren’t as nice looking - in fact, they are “the first 32 bits of the fractional parts of the square roots of the first eight prime numbers” according to the RFC. Hence, to make your own variant of SHA-256, you should look for the fractional parts of some other eight prime numbers.

Pad the message.

size_t messageSize;

uint8_t* message = sha2_pad(msg, size, &messageSize);

Copy the 64 bytes in the block into the first 16 words of the temporary buffer, W, using a platform-agnostic way to preserve big endianness.

for (int i = 0; i < messageSize; i += 64) {

int t;

const uint8_t* block = message + i;

SHA2_WORD W[64];

for (t = 0; t < 16; t++) {

W[t] = block[t * 4] << 24;

W[t] |= block[t * 4 + 1] << 16;

W[t] |= block[t * 4 + 2] << 8;

W[t] |= block[t * 4 + 3];

}

Calculate the rest of the WORDS in W with the algorithm specified in RFC 6234.

for (t = 16; t < 64; t++) {

W[t] = sha2_SSIG1(W[t - 2]) + W[t - 7] + sha2_SSIG0(W[t - 15]) + W[t - 16];

}

SHA-256 uses two temporary buffers alongside the intermediary variables A to H. The outline of the algorithm is also described in the RFC, and so the code here is just the “translated” version.

SHA2_WORD A = h0;

SHA2_WORD B = h1;

SHA2_WORD C = h2;

SHA2_WORD D = h3;

SHA2_WORD E = h4;

SHA2_WORD F = h5;

SHA2_WORD G = h6;

SHA2_WORD H = h7;

SHA2_WORD T1, T2;

for (t = 0; t < 64; t++) {

T1 = H + sha2_BSIG1(E) + sha2_CH(E, F, G) + SHA2_K[t] + W[t];

T2 = sha2_BSIG0(A) + sha2_MAJ(A, B, C);

H = G;

G = F;

F = E;

E = D + T1;

D = C;

C = B;

B = A;

A = T1 + T2;

}

As per usual with normal digest algorithms, we add the intermediary values back to h0 to h7.

h0 += A;

h1 += B;

h2 += C;

h3 += D;

h4 += E;

h5 += F;

h6 += G;

h7 += H;

}

While a little more inefficient, I decided to use a for-loop over writing 64 lines of code to convert h0 to h7 into a byte array. A faster implementation would be to write all 64 lines, so that the compiler doesn’t generate JMP instructions which is usually slower to execute.

free(message);

uint8_t* retVal = (uint8_t*) malloc(32);

SHA2_WORD* retValView = (SHA2_WORD*) retVal;

retValView[0] = h0;

retValView[1] = h1;

retValView[2] = h2;

retValView[3] = h3;

retValView[4] = h4;

retValView[5] = h5;

retValView[6] = h6;

retValView[7] = h7;

// platform agnostic big-endian

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++) {

SHA2_WORD temp = retValView[i];

retVal[i * 4 + 3] = temp;

retVal[i * 4 + 2] = temp >> 8;

retVal[i * 4 + 1] = temp >> 16;

retVal[i * 4] = temp >> 24;

}

return retVal;

}

The code is available on my GitHub repository.

SHA-512 (Optional)

In SHA-512, the function return a 512-bit string based on 1024-bit blocks of data. SHA-512 also uses 64-bit words, which means that we have to use uint64_t over uint32_t.

From RFC 6234, the magic number array, K, is defined as:

const SHA512_WORD sha512_K[] = {

0x428a2f98d728ae22, 0x7137449123ef65cd, 0xb5c0fbcfec4d3b2f, 0xe9b5dba58189dbbc,

0x3956c25bf348b538, 0x59f111f1b605d019, 0x923f82a4af194f9b, 0xab1c5ed5da6d8118,

0xd807aa98a3030242, 0x12835b0145706fbe, 0x243185be4ee4b28c, 0x550c7dc3d5ffb4e2,

0x72be5d74f27b896f, 0x80deb1fe3b1696b1, 0x9bdc06a725c71235, 0xc19bf174cf692694,

0xe49b69c19ef14ad2, 0xefbe4786384f25e3, 0x0fc19dc68b8cd5b5, 0x240ca1cc77ac9c65,

0x2de92c6f592b0275, 0x4a7484aa6ea6e483, 0x5cb0a9dcbd41fbd4, 0x76f988da831153b5,

0x983e5152ee66dfab, 0xa831c66d2db43210, 0xb00327c898fb213f, 0xbf597fc7beef0ee4,

0xc6e00bf33da88fc2, 0xd5a79147930aa725, 0x06ca6351e003826f, 0x142929670a0e6e70,

0x27b70a8546d22ffc, 0x2e1b21385c26c926, 0x4d2c6dfc5ac42aed, 0x53380d139d95b3df,

0x650a73548baf63de, 0x766a0abb3c77b2a8, 0x81c2c92e47edaee6, 0x92722c851482353b,

0xa2bfe8a14cf10364, 0xa81a664bbc423001, 0xc24b8b70d0f89791, 0xc76c51a30654be30,

0xd192e819d6ef5218, 0xd69906245565a910, 0xf40e35855771202a, 0x106aa07032bbd1b8,

0x19a4c116b8d2d0c8, 0x1e376c085141ab53, 0x2748774cdf8eeb99, 0x34b0bcb5e19b48a8,

0x391c0cb3c5c95a63, 0x4ed8aa4ae3418acb, 0x5b9cca4f7763e373, 0x682e6ff3d6b2b8a3,

0x748f82ee5defb2fc, 0x78a5636f43172f60, 0x84c87814a1f0ab72, 0x8cc702081a6439ec,

0x90befffa23631e28, 0xa4506cebde82bde9, 0xbef9a3f7b2c67915, 0xc67178f2e372532b,

0xca273eceea26619c, 0xd186b8c721c0c207, 0xeada7dd6cde0eb1e, 0xf57d4f7fee6ed178,

0x06f067aa72176fba, 0x0a637dc5a2c898a6, 0x113f9804bef90dae, 0x1b710b35131c471b,

0x28db77f523047d84, 0x32caab7b40c72493, 0x3c9ebe0a15c9bebc, 0x431d67c49c100d4c,

0x4cc5d4becb3e42b6, 0x597f299cfc657e2a, 0x5fcb6fab3ad6faec, 0x6c44198c4a475817

};

Which are the same eighty prime numbers used in SHA-256, only with more digits representing the fractional parts of the cube roots.

The binary functions are also quite similar to that in SHA-256, with a few numbers tweaked for working with SHA-512’s comparatively massive WORD and block size:

SHA512_WORD sha512_ROTR(SHA512_WORD X, uint8_t n) {

return (X >> n) | (X << (64 - n));

}

SHA512_WORD sha512_CH(SHA512_WORD X, SHA512_WORD Y, SHA512_WORD Z) {

return (X & Y) ^ ((~X) & Z);

}

SHA512_WORD sha512_MAJ(SHA512_WORD X, SHA512_WORD Y, SHA512_WORD Z) {

return (X & Y) ^ (X & Z) ^ (Y & Z);

}

SHA512_WORD sha512_BSIG0(SHA512_WORD X) {

return sha512_ROTR(X, 28) ^ sha512_ROTR(X, 34) ^ sha512_ROTR(X, 39);

}

SHA512_WORD sha512_BSIG1(SHA512_WORD X) {

return sha512_ROTR(X, 14) ^ sha512_ROTR(X, 18) ^ sha512_ROTR(X, 41);

}

SHA512_WORD sha512_SSIG0(SHA512_WORD X) {

return sha512_ROTR(X, 1) ^ sha512_ROTR(X, 8) ^ (X >> 7);

}

SHA512_WORD sha512_SSIG1(SHA512_WORD X) {

return sha512_ROTR(X, 19) ^ sha512_ROTR(X, 61) ^ (X >> 6);

}

The algorithm for padding is still the same as that in SHA-1, except that the numbers must be adjusted for SHA-512 due to the change in the block size. As a quick reference, 1024-bits is 128 bytes. This is evident below:

uint8_t* sha512_pad(const void* msg, size_t size, size_t* newSize) {

if (!msg) {

return 0;

}

size_t toPad = 128 - (size % 128);

if (toPad < 17) {

toPad += 128;

}

uint8_t* newArr = (uint8_t*) malloc(size + toPad);

memcpy(newArr, msg, size);

newArr[size] = 0x80;

memset(newArr + size + 1, 0x00, toPad - 16);

const uint64_t lowerSizeInBits = size * 8; // whatever can be captured will be captured

const uint64_t upperSizeInBits = size >> 61; // this is (size >> 64) * 8

const uintptr_t ptr = size + toPad - 16;

newArr[ptr] = upperSizeInBits >> 56;

newArr[ptr + 1] = upperSizeInBits >> 48;

newArr[ptr + 2] = upperSizeInBits >> 40;

newArr[ptr + 3] = upperSizeInBits >> 32;

newArr[ptr + 4] = upperSizeInBits >> 24;

newArr[ptr + 5] = upperSizeInBits >> 16;

newArr[ptr + 6] = upperSizeInBits >> 8;

newArr[ptr + 7] = upperSizeInBits;

newArr[ptr + 8] = lowerSizeInBits >> 56;

newArr[ptr + 9] = lowerSizeInBits >> 48;

newArr[ptr + 10] = lowerSizeInBits >> 40;

newArr[ptr + 11] = lowerSizeInBits >> 32;

newArr[ptr + 12] = lowerSizeInBits >> 24;

newArr[ptr + 13] = lowerSizeInBits >> 16;

newArr[ptr + 14] = lowerSizeInBits >> 8;

newArr[ptr + 15] = lowerSizeInBits;

if (newSize) {

*newSize = size + toPad;

}

return newArr;

}

Now with all that out of the way, let’s do the hashing process.

Like SHA-256, these numbers are extracted from the fractional parts of the first eight prime numbers, only with more digits representing the fraction.

uint8_t* sha512(const void* msg, size_t size) {

SHA512_WORD h0 = 0x6a09e667f3bcc908;

SHA512_WORD h1 = 0xbb67ae8584caa73b;

SHA512_WORD h2 = 0x3c6ef372fe94f82b;

SHA512_WORD h3 = 0xa54ff53a5f1d36f1;

SHA512_WORD h4 = 0x510e527fade682d1;

SHA512_WORD h5 = 0x9b05688c2b3e6c1f;

SHA512_WORD h6 = 0x1f83d9abfb41bd6b;

SHA512_WORD h7 = 0x5be0cd19137e2179;

Pad the message so that we have full 1024-bit blocks to work with.

size_t messageSize;

uint8_t* message = sha512_pad(msg, size, &messageSize);

Copy the message into a temporary 80-byte buffer, W with a platform-agnostic way of maintaining endianness. Because WORD sizes are 64-bits in SHA-512 instead of 32-bits in SHA-256, 8 bytes can fit within one WORD, which is why this block of code is 4 lines longer than that in the implementation of SHA-256.

for (int i = 0; i < messageSize; i += 128) {

int t;

const uint8_t* block = message + i;

SHA512_WORD W[80];

for (t = 0; t < 16; t++) {

W[t] = (SHA512_WORD) block[t * 8] << 56;

W[t] |= (SHA512_WORD) block[t * 8 + 1] << 48;

W[t] |= (SHA512_WORD) block[t * 8 + 2] << 40;

W[t] |= (SHA512_WORD) block[t * 8 + 3] << 32;

W[t] |= (SHA512_WORD) block[t * 8 + 4] << 24;

W[t] |= (SHA512_WORD) block[t * 8 + 5] << 16;

W[t] |= (SHA512_WORD) block[t * 8 + 6] << 8;

W[t] |= (SHA512_WORD) block[t * 8 + 7];

}

Fill up the remaining data with the algorithm specified by the RFC, which should be almost identical to that of SHA-256.

for (t = 16; t < 80; t++) {

W[t] = sha512_SSIG1(W[t - 2]) + W[t - 7] + sha512_SSIG0(W[t - 15]) + W[t - 16];

}

Main computation steps, which should be identical to that of SHA-256.

SHA512_WORD A = h0;

SHA512_WORD B = h1;

SHA512_WORD C = h2;

SHA512_WORD D = h3;

SHA512_WORD E = h4;

SHA512_WORD F = h5;

SHA512_WORD G = h6;

SHA512_WORD H = h7;

SHA512_WORD T1, T2;

for (t = 0; t < 80; t++) {

T1 = H + sha512_BSIG1(E) + sha512_CH(E, F, G) + sha512_K[t] + W[t];

T2 = sha512_BSIG0(A) + sha512_MAJ(A, B, C);

H = G;

G = F;

F = E;

E = D + T1;

D = C;

C = B;

B = A;

A = T1 + T2;

}

Accumulate the intermediary variables into h0 to h7 as usual.

h0 += A;

h1 += B;

h2 += C;

h3 += D;

h4 += E;

h5 += F;

h6 += G;

h7 += H;

}

Perform some memory management, and copy h0 to h7 in a platform-agnostic way to preserve big-endianness. The full code can be found in my GitHub repository.

free(message);

uint8_t* retVal = (uint8_t*) malloc(128);

SHA512_WORD* retValView = (SHA512_WORD*) retVal;

retValView[0] = h0;

retValView[1] = h1;

retValView[2] = h2;

retValView[3] = h3;

retValView[4] = h4;

retValView[5] = h5;

retValView[6] = h6;

retValView[7] = h7;

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++) {

SHA512_WORD temp = retValView[i];

retVal[i * 8] = temp >> 56;

retVal[i * 8 + 1] = temp >> 48;

retVal[i * 8 + 2] = temp >> 40;

retVal[i * 8 + 3] = temp >> 32;

retVal[i * 8 + 4] = temp >> 24;

retVal[i * 8 + 5] = temp >> 16;

retVal[i * 8 + 6] = temp >> 8;

retVal[i * 8 + 7] = temp;

}

return retVal;

}

HMAC

At this point, a possible TOTP implementation might be to simply hash the current time with a symmetric key, truncate that hash, return 6 to 8 digits and call it a day. This is quite similar to the current modern-day implementation of OTP, albeit using internet standards that already exist.

While hashes are used to tell us about the contents of information in the form of a digest, Hash-based Message Authentication Codes (HMACs) are a way to check:

- The authenticity (i.e. is the person sending the message who I expect it to be?) of the content;

- The integrity (i.e. has it been modified?) of the content.

Lets say Bob wants to send a message to Alice, with HMAC as a way to verify and authenticate the message:

- Bob and Alice exchange a shared secret, perhaps through the Diffie-Hellman key exchange, or going retro-style and exchanging it physically with paper and pen;

- Bob writes a message, uses a hash algorithm like SHA-256 and combines it with the shared secret in a manner described in RFC 2104 to produce a HMAC;

- Bob sends the resulting message and HMAC to Alice, perhaps through two independent communication channels;

- Alice receives the message, uses a hash algorithm like SHA-256, combines it with the shared secret that was given to her in Step 1, and computes her own HMAC;

- Alice compares her HMAC to the HMAC generated by Bob;

- If the HMAC matches, she knows that the message was definitely written by Bob, and her message integrity is intact and not maliciously modified by a third party.

From the above description, one can gather that HMACs have two components:

- The hash function; and

- The shared key.

In truth, while HMAC might be surrounded in mystery and seem like a difficult algorithm, it cannot get easier to implement:

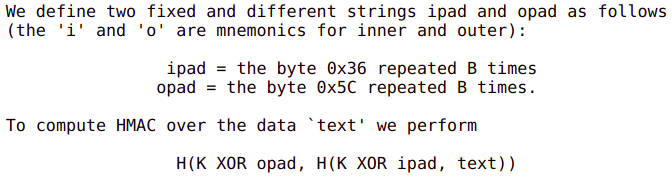

HMAC algorithm | Source: RFC 2104

Moreover, the padding for the key is dead-simple: append 0x00 until the key equals the block size of the hashing algorithm. RFC 2104 is a very ancient RFC, and hence only mentions MD5 and SHA-1 as possible hashing algorithms; in truth, any modern-day hashing algorithms can be used.

Without further ado, here is the code for padding:

uint8_t* hmac_pad(uint8_t* input, size_t size, size_t blockSize) {

uint8_t* retVal = (uint8_t*) malloc(blockSize);

memcpy(retVal, input, size);

memset(retVal + size, 0x00, blockSize - size);

return retVal;

}

As for the HMAC code, let’s do it step by step. HMAC might not be a complicated algorithm, but it can look quite scary at first. Case in point, look at the function signature:

uint8_t* hmac(const void* msg, size_t size, const void* K, size_t keySize, void* (*H)(const void*, size_t), size_t blockSize, size_t outputLength) {

uint8_t* workingKey = (uint8_t*) K;

if (keySize > blockSize) {

uint8_t *temp = (uint8_t*) H(K, keySize);

workingKey = hmac_pad(temp, outputLength, blockSize);

free(temp);

} else {

workingKey = hmac_pad(workingKey, keySize, blockSize);

}

The function accepts a message, the message size, a key, the key size, a hash function, the hash’s block size in bytes, and the hash’s output length in bytes. So many parameters to mess up! Typically, just like the hashes, all the parameters are enclosed in a structure, such that you only need to pass a single structure to the function and call a digest function for each block of the message; however, as our goal is to generate an OTP from a fixed length key, I figured that it was not necessary.

The above code pads the key if the key is not wide enough; otherwise, if the key is too long, it will be hashed down first before padding, as specified in the RFC.

uint8_t *intermediate1 = (uint8_t*) malloc(blockSize);

uint8_t *intermediate2 = (uint8_t*) malloc(blockSize);

for (int i = 0; i < blockSize; i++) {

intermediate1[i] = workingKey[i] ^ 0x36;

intermediate2[i] = workingKey[i] ^ 0x5c;

}

I will admit, this is not my best work; creating tons of intermediate variables just to compute a HMAC is probably very resource-wasteful. However, I didn’t care to optimize the code further than I have to, in effort to prevent me from losing interest. The code above hashes what the RFC defines as ipad, a block of 0x36, and opad, a block of 0x5c, to the key, storing the results in intermediate variables to be used later. In short, these compute K XOR opad and K XOR ipad.

To overcome the oversight of not having a streamable hashing function, I had to concatenate the result of K XOR ipad with the message before I could perform any hashing operations on it. The code computes K XOR ipad, text.

uint8_t *intermediate3 = (uint8_t*) malloc(blockSize + size);

memcpy(intermediate3, intermediate1, blockSize);

memcpy(intermediate3 + blockSize, msg, size);

This computes H(K XOR ipad, text).

uint8_t *intermediate4 = (uint8_t*) H(intermediate3, blockSize + size);

Again, due to the oversight of not having a streamable hashing function, I concatenated the result of H(K XOR ipad, text) to K XOR opad to produce K XOR opad, H(K XOR ipad, text).

uint8_t *intermediate5 = (uint8_t*) malloc(blockSize + outputLength);

memcpy(intermediate5, intermediate2, blockSize);

memcpy(intermediate5 + blockSize, intermediate4, outputLength);

Finally, this line computes H(K XOR opad, H(K XOR ipad, text)).

uint8_t *result = (uint8_t*) H(intermediate5, blockSize + outputLength);

All that is left is to free all the intermediate variables, and return the result:

free(intermediate1);

free(intermediate2);

free(intermediate3);

free(intermediate4);

Pfree(intermediate5);

free(workingKey);

return result;

And presto, we’ve implemented HMAC! I used this online tool to test the same HMAC implementation on the SHA-256 and SHA-512 algorithms. To call this function, we have to do the following:

#include "hmac.h"

// include only one of these

#include "sha1.h"

#include "sha256.h"

#include "sha512.h"

int main() {

const char message[] = "the quick brown fox jumped over the lazy sleeping dog";

const char key[] = "epic key";

// sha1

const uint8_t* result = hmac(message, sizeof(message) - 1, key, sizeof(key) - 1, (void* (*) (const void*, size_t)) method_two, 64, 20);

// sha256

const uint8_t* result = hmac(message, sizeof(message) - 1, key, sizeof(key) - 1, (void* (*) (const void*, size_t)) sha256, 64, 32);

// sha512

const uint8_t* result = hmac(message, sizeof(message) - 1, key, sizeof(key) - 1, (void* (*) (const void*, size_t)) sha512, 128, 64);

// do whatever with result

free(result);

return 0;

}

In case you were wondering what the numbers 20, 32, 64, and 128 mean, you may recall that:

- SHA1 has a 512-bit block size (64 bytes) and 160-bit result (20 bytes)

- SHA256 has a 512-bit block size (64 bytes) and 256-bit result (32 bytes)

- SHA512 has a 1024-bit block size (128 bytes) and 512-bit result (64 bytes)

The code is available on my GitHub repository.

HOTP

With HMAC implemented, we can finally implement RFC 4226, one step shy of our goal to get TOTPs! Being one step away from TOTPs, HOTPs are counter-based, meaning that the end-user would need to manually increment a counter to generate the next OTP used for authentication.

You can probably already see how to generate TOTPs from HOTPs, but for the sake of completeness, let’s talk about how HOTP works. With the HMAC algorithm, we need to specific a message and the key; in the context of HOTPs, the message would be the counter value, and the key would be an actual cryptographic secret. From there, we would get a unique value from HMAC every increment of the counter. However, even though getting the user to type 20 hexadecimal numbers might be a fun way to torture them, we have to think about practicality, and instead choose to truncate the value produced by the HMAC algorithm.

In other words, HOTP is defined as HOTP(K,C) = Truncate(HMAC-SHA-*(K, C)), where K is the key, C is the counter value, HMAC-SHA-* is any SHA family hashing algorithm, and Truncate is the truncation function that will cut our value short, and produce 6 to 8 digits of user-friendly numbers for their consumption.

Luckily for us, Truncate has a simple definition. Given the hash result, H, in byte array form, arranged in Big Endian:

- Obtain the last 4 bits in the last byte within

H, i.e.H[len(H) - 1]; - Convert (if necessary) the numerical value of the 4 bits (i.e. 0101 base 2 is 5 base 10) to a number,

i; - Define a 4-byte variable and assign it to contain the values, in native byte order,

H[i]toH[i + 3]; - Mask the first bit of the 4-byte variable, and modulo it with 10^(number of digits in OTP) to obtain a 6 to 8 digit number OTP.

Sounds complicated? Well, programmers like to see code, so here you go:

uint32_t hotp_DT(const uint8_t* data, size_t len) {

uint8_t offset = data[len - 1] & 0x0f;

uint32_t p = (data[offset] & 0x7f) << 24

| data[offset + 1] << 16

| data[offset + 2] << 8

| data[offset + 3];

return p;

}

Dead-simple, I tell you. Words are meaningless constructs in the face of code, unless functional programming is involved.

For the actual HOTP algorithm, I figured to use a structure for once:

typedef struct {

uint64_t counter;

const uint8_t* secret;

size_t secretSize;

void* (*hashFn)(const void*, size_t);

size_t blockSize;

size_t outputLength;

} hotp_context;

Using uint64_t for the counter might seem overkill, but the size of the counter is defined in the RFC; it makes sense too, because later on in TOTP, we are going to need uint64_t, as storing time in a uint32_t variable will be a bad idea closer to the year 2038. Let’s work on the HOTP algorithm itself.

Since we have a 64-bit counter of unknown byte order, we need to first break it down into a Big Endian byte array.

uint32_t hotp(hotp_context *ctx, uint8_t digits) {

if (!ctx) {

return 0;

}

uint8_t counter[8];

counter[0] = ctx->counter >> 56;

counter[1] = ctx->counter >> 48;

counter[2] = ctx->counter >> 40;

counter[3] = ctx->counter >> 32;

counter[4] = ctx->counter >> 24;

counter[5] = ctx->counter >> 16;

counter[6] = ctx->counter >> 8;

counter[7] = ctx->counter;

We then run the counter and secret through HMAC, which computes HMAC-SHA-*(K, C).

uint8_t* hs = hmac(counter, sizeof(counter), ctx->secret, ctx->secretSize, ctx->hashFn, ctx->blockSize, ctx->outputLength);

Truncating it with the function we wrote earlier, we get our close to final result.

uint32_t Snum = hotp_DT(hs, ctx->outputLength);

All we need to do now is to perform memory cleanup, and return the number of digits we desire from the algorithm:

free(hs);

return Snum % (uint32_t) pow(10.0, digits);

}

To use the hotp function, the following C code can be used:

#include "sha1.h"

#include "hotp.h"

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

const char secret[] = "a very secret key!!!";

hotp_context ctx;

ctx.secret = (const uint8_t*) secret;

ctx.secretSize = sizeof(secret) - 1;

ctx.hashFn = (void* (*) (const void*, size_t)) method_two;

ctx.blockSize = 64;

ctx.outputLength = 20;

printf("%d\n", hotp(&ctx, 6));

return 0;

}

Refer to the HMAC section to change the values of ctx.hashFn, ctx.blockSize and ctx.outputLength. The full C code can be found in my GitHub repository.

TOTP

And finally, RFC 6238, the whole purpose of this blog post. TOTPs! HOTPs are slightly troublesome, requiring the user to increment the counter manually - this meant that receivers of HOTP needed to define an interval of OTPs that they’ll accept, through the resynchronization parameter. This is error-prone, and highly frustrating for the end-user, especially due to off-by-one errors and naughty toddlers incrementing HOTP counters.

TOTPs solve this problem by using Real-Time clocks available on most low-powered hardware, and relatively high-powered devices like smart phones and laptops - they use time as a means to calculate the counter value in HOTP. In other words, TOTP can be said to be a simple extension of HOTPs.

In TOTPs, two more parameters are defined:

-

T0, the “beginning” time to consider, which is defaults to 0, representing UNIX Epoch; -

X, the time-step to consider, which defaults to 30 seconds.

The counter value is defined as (timestamp in seconds - T0) / X, and the key is still an actual cryptographic key.

As such, the implementation of TOTP is extremely trivial:

uint32_t totp(hotp_context *ctx, uint8_t digits = 6) {

time_t now = time(NULL);

ctx->counter = (now - T0) / X;

return hotp(ctx, digits);

}

Bam. Done. That’s TOTP, RFC 6238. The RFC also talks about time drift and whatnot, but since we are generating OTPs, it shouldn’t be too much of a bother for us. You can test the totp implementation with:

#include "sha1.h"

#include "hotp.h"

#include "totp.h"

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

const char secret[] = "a very secret key!!!";

hotp_context ctx;

ctx.secret = (const uint8_t*) secret;

ctx.secretSize = sizeof(secret) - 1;

ctx.hashFn = (void* (*) (const void*, size_t)) method_two;

ctx.blockSize = 64;

ctx.outputLength = 20;

printf("%d\n", totp(&ctx, 6));

return 0;

}

The OTP generated by the code written so far matches with the TOTP generator written by Dan Hersam. Do note that Dan’s site uses Base32 keys, so you’ll need a Base32 encoder; make sure to remove all the padding before using it as a key (i.e. delete all the =).

Why? Dan’s implementation of TOTP relies on a library called

otpauthon versionv3.1.3. In line 143 of this version’s utility function, where base32 is encoded into anArrayBuffer, the padding characters,=are not handled at all, leading to an error that causes the token to be generated wrongly. This is fixed in a subsequent version ofotpauth, but unfortunately, Dan has since stopped maintaining the TOTP generator.

The code for TOTP can be found on my GitHub repository.

Conclusion

Implementing TOTP from all of its components was quite a journey for me. In the modern world, we build great-scaled applications on the shoulders of giants - libraries do most of our heavy lifting. However, it is important to visit the low-level once in a while to marvel at the smaller building blocks, understand design considerations behind every line of code, and take it all in as an art-form.

Some day, new algorithms will be developed in favour of whatever we use today; surely, they will have more extensive use-cases only imaginable by those of the future.

Let’s see what tomorrow brings!

Happy Coding

CodingIndex