A (human) index that likes to code

Also drinks way too much coffee ![]()

I implemented AES and MD5

Published Dec 05, 2020 15:30

For many people, encryption is a magic black box that turns plaintext into ciphertext, via the use of a shared secret key. It is a way to privately share information through the internet, which, by nature of publicly exposed wires, is susceptible to eavesdropping. It is no wonder encryption became the cornerstone for secure internet banking, e-government transactions, and one of the strongest anti-snooping & anti-surveillance weapon society has today. Without encryption, anyone and everyone can simply tap onto the wire, steal your passwords, identity and money.

Then there are message digests; When you go online to shop for PC video games or software, how does your fancy Windows User Account Control know that an executable is from a verified publisher?

Windows UAC | Source: Comodo SSL Store

The long answer involves public key cryptography, an expensive certificate to buy, and verifying the signature of file hashes; but the short answer, is via file hashes. After all, a signature is a file hash encrypted by the private key, and hashes are used to figure out if an executable is the real deal. For the most part, a hash is a one-way function, which turns a large chunk of data into a 128-bit blob that represents the data; in other words, if you wanted to know that a hacker hasn’t done anything sketchy to an executable, simply run it through a hash function, and compare the hash output with a reliable source.

In this blog post, I unravel the two black boxes. I try to understand the mathematics and implement the most famous, and most used encryption algorithm on the planet: AES. As a bonus, I also implement the MD5 hash algorithm.

AES

AES is actually an algorithm name granted to the Rijndael encryption algorithm by NIST, after a voting process and cryptanalysis. Think of it like calling an emperor by “Your Majesty” instead of his/her real name. You can read more about the AES process here.

Canonically, there are three key sizes (128, 192, or 256 bits) and only one block size (128 bits). Since AES is a block cipher, and plaintext is something that is practically arbitrary-lengthed, they need to be operated in a mode to encrypt data in the real world. My personal guess for the most popular mode used in AES is probably the Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) mode; you can read more about the different modes in this article by Shawn Wang.

While most things that need encryption use AES-256 on CBC mode nowadays, I will only implement the AES-128 block cipher with no modes as most of the educational value is in the block cipher. The repository for the AES implementation can be found through this link.

Step 0: Research

Before I got the idea to implement and understand the math behind AES, I had no idea what was in store for me. However, I recalled having seen a stick figure comic about AES before, and went ahead to read it.

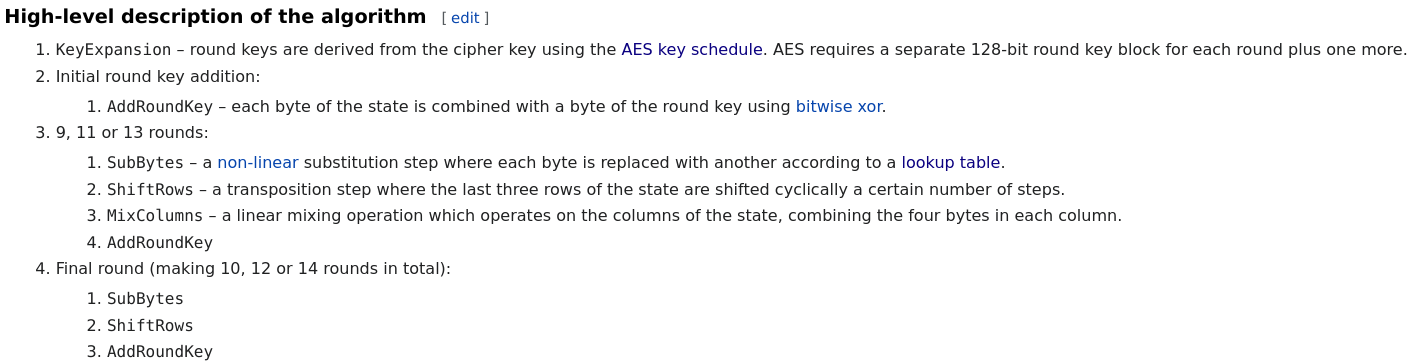

After some more supplementary reading from the Wikipedia article on AES, I realized that there are 5 main steps in the AES cipher:

- KeyExpansion - Expands a 128-bit key into round keys used throughout the cipher;

- AddRoundKey - Combines the state and round key together;

- ShiftRows - Offsets the last words by individual bytes;

- SubBytes - Substitutes bytes via a lookup table;

- MixColumns - Swaps bytes around, multiplies them a little, etc.

Let’s understand some terminology.

| Phrase | Layman Description |

|---|---|

| Round | Rounds are just a collection of steps repeated for a certain number of times. In the case of AES-128, there are 10 rounds in total. |

| Key Expansion | With the 128-bit key, do some mathematics to derive keys used in each round. |

| Round Key | The key used for a specific round. The first round key will always be the user-supplied key. |

| State | The block of data that we are working with. At first, the state will be your plaintext; as we go through the rounds, the state changes and eventually becomes the ciphertext. |

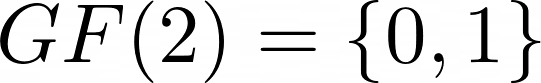

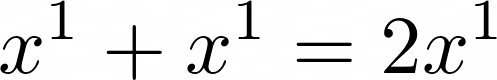

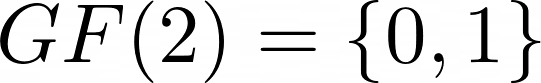

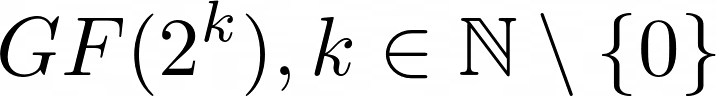

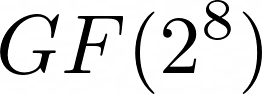

I poked around the Wikipedia article, clicking into links to understand more about the AES Key Schedule, and how the mathematics worked. This led me to learn about the finite field, or more fancifully known as the Galois field. In a nutshell, a finite field contains a finite number of elements, which will always be a prime or a power of a prime. A finite field of 2 will contain the elements 0 and 1, i.e.  , while a finite field of 3 will contain the elements 0, 1 and 2, i.e.

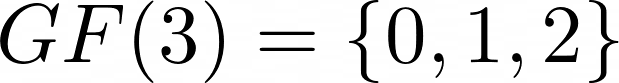

, while a finite field of 3 will contain the elements 0, 1 and 2, i.e.  . What we are particularly interested in is finite fields defined by

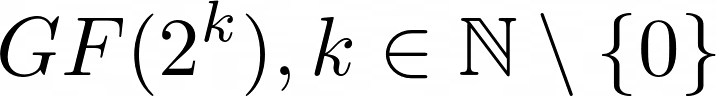

. What we are particularly interested in is finite fields defined by  , because all extension fields (i.e. any

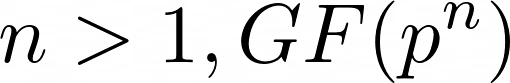

, because all extension fields (i.e. any k that satisfies the condition in the equation) have the same rules of arithmetic (i.e. addition, division, multiplication and subtraction). Before we dive into why having the same rules of arithmetic is important to AES, it is worth it to mention that if  for any prime

for any prime p, then the finite field can be expressed as a polynomial, where the coefficients are in the  field, which will be used like free flowing cash in AES. You can read more about finite fields through this Wolfram article.

field, which will be used like free flowing cash in AES. You can read more about finite fields through this Wolfram article.

Why same rules of arithmetic is important to AES

XOR gates. They’re great, fast, efficient, and easy to implement. So, wouldn’t it be great to encryption performance if it’s used to heck and back in AES?

That is what living within the  finite field allows us to do. In this particular field, which you recall, can be expressed as a polynomial with co-efficients in the

finite field allows us to do. In this particular field, which you recall, can be expressed as a polynomial with co-efficients in the  field. Here is a polynomial in

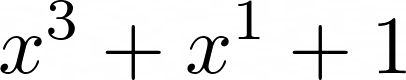

field. Here is a polynomial in  :

:

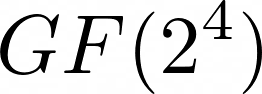

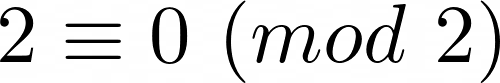

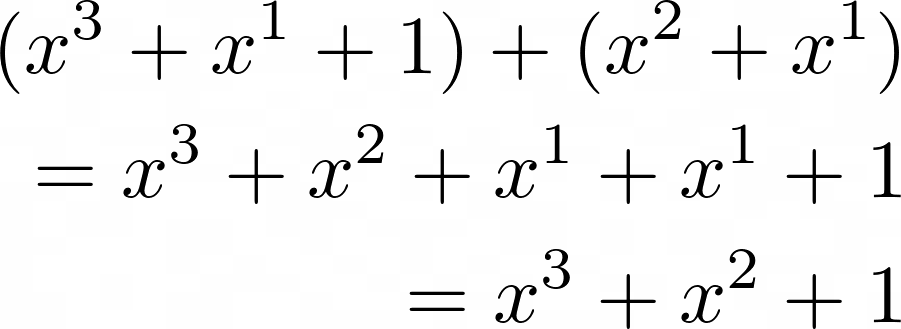

The co-efficients cannot be anything else but 0 and 1. This means that we can represent the co-efficients of this polynomial with binary: 1011. Let’s try adding two polynomials together across the  field:

field:

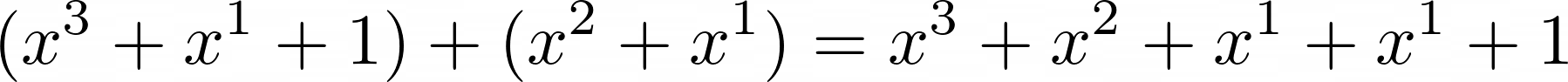

Ah, what do we do now? We are trying to add two  together. Recall that the co-efficients can only be 0 and 1; in the rules of normal mathematics, we would have been able to just add the two co-efficients together:

together. Recall that the co-efficients can only be 0 and 1; in the rules of normal mathematics, we would have been able to just add the two co-efficients together:  . However, this is not normal mathematics; we have to give our answer in terms of the finite field

. However, this is not normal mathematics; we have to give our answer in terms of the finite field  . So, we take the would-be-co-efficient, and modulo it by 2 (formally,

. So, we take the would-be-co-efficient, and modulo it by 2 (formally,  ).

).

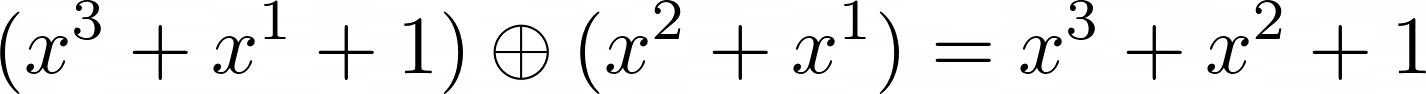

If you turn the co-efficients of the operands into binary and squint your eyes ever so slightly, you’ll realize that adding the two polynomials it’s basically just XORing two binary numbers: 1011 ^ 0110 = 1101! And so, modifying our math equations one last time with the XOR operator:

Beautiful. We now know that adding two polynomials within  fields is essentially just XORing the coefficients in binary form.

fields is essentially just XORing the coefficients in binary form.

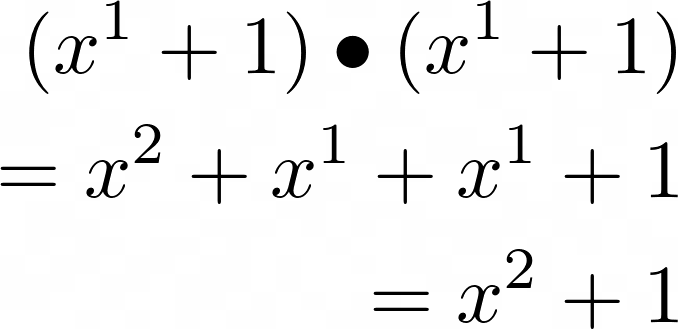

What about multiplication between two polynomials? Let’s take a look at the multiplication between these two polynomials in same finite field.

Converting it to binary, we see: 0011 * 0011 = 0101 which, when converted to decimal numbers, means that 3 * 3 = 5. Math is broken, I’m retiring, good night forever.

Retiring forever | Source: Giphy

Turns out, this kind of multiplication is known as carry-less product. The technique detailed in the link allows us to perform our multiplication with our best friend, XOR, within any extension field of  .

.

Apart from a tiny bit of matrix multiplication, that is all of the mathematics we need to know to work with AES.

Step 1: SBox

Let’s implement an SBox. An SBox, or substitution box, is used to introduce confusion into cipher. It’s also part of key expansion, which is the first major step in AES. For educational purposes, I did not copy the SBox table off Wikipedia; instead, I ripped off the pseudo-code implementation on the same Wikipedia page.

Of course, I took time to think about what exactly I was doing with the code. Let’s go through my resulting JavaScript code segment by segment.

let p = 1, q = 1;

What is important in the above block of code is not the variable declaration, but the fact that p * q == 1 always - for every change to p, we must calculate a reciprocal of it and store it in q. The equation, p * q == 1 is known as a Galois field invariant. We want to iterate through every element in the field to generate a full SBox, but we don’t have to do it in sequential order.

do {

p = (p ^ ((p << 1) % 2**8) ^ (p & 0x80 ? 0x1B : 0)) % 2**8;

In this line, we are (carry-less) multiplying by 3, in efforts to iterate through every element in the field. Other numbers can also be chosen, like 2. % 2**8 is used to clip for the integers to stay within the limits of a byte, since there is no byte data type in JavaScript. In carry-less multiplication, we do the following:

- Figure out the positions of the bit

1in the number3:0011, which means that there are bit1s in position 1 and 0. - Without modifying

p(i.e. make a copy), shiftpleft by those amount of positions for each bit1. This means shifting two copies ofp, one time once to the left, the other 0 times to the left. - XOR all copies of

pand assign it back intop. In other words:p = p ^ (p << 1).

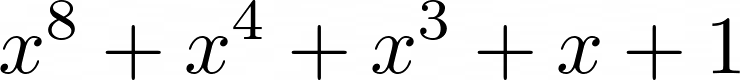

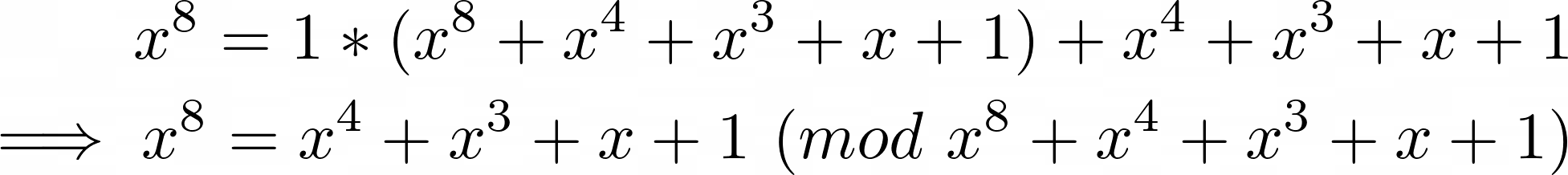

That explains the front portion. What about the (p & 0x80 ? 0x1B : 0) part? The mathematical notation of our field is ![GF(2^8) = GF(2)[x]/(x^8 + x^4 + x^3 + x + 1)](/images/20201205_18.png) , where

, where  is the irreducible polynomial. An irreducible polynomial is something that cannot be reduced further to multiplications of two elements within the finite field, and is absolutely magical, because it can also generate all possible polynomials within a field. Remember that we shifted

is the irreducible polynomial. An irreducible polynomial is something that cannot be reduced further to multiplications of two elements within the finite field, and is absolutely magical, because it can also generate all possible polynomials within a field. Remember that we shifted p 1 position to the left? If the most significant bit was a 1 and it was shifted away, we need to account for it somehow, right? However, since that bit represents a co-efficient of  , which is too large to fit within our finite field, we must reduce it with the irreducible polynomial (i.e. generate the equivalent within our field) by modulo. Turns out:

, which is too large to fit within our finite field, we must reduce it with the irreducible polynomial (i.e. generate the equivalent within our field) by modulo. Turns out:

The multiplication of 1 on the right hand side of the first line is a guess. You can get this number without guessing by using the Extended Euclidean Algorithm, but to be honest I have no idea how and I can’t be bothered to find out. Regardless, the above equations matches with our 0x1B binary representation perfectly!

q ^= q << 1;

q ^= q << 2;

q ^= q << 4;

// https://math.stackexchange.com/a/1231243 for why 0x09

q ^= (q) & 0x80 ? 0x09 : 0;

q %= 2**8;

Here, we are dividing by 3, which is the same as multiplying by the inverse of 3. Using the power of mathematics, we see that:

Which means that 0xf6 is an inverse of 0x03 (remember that p * q == 1 Galois Invariant?)! When performing the arcane art of carry-less multiplication, we find that there is no point shifting after 4. This is because the next shift, 8, would just shift the entirety of q out of existence (i.e. becomes 0x00 after shifting), wasting CPU cycles for calculation. The missing co-efficients as a result of ignoring shifts after 4 is fixed later on with the line q ^= (q) ^ 0x80 ? 0x09 : 0. The author of a StackOverflow answer explains how the mystery number, 0x09 is derived better than I can, so do check out his answer.

Now that we have calculated p and q, we can continue following the instructions on deriving the SBox. In essence, we use the multiplicative inverse of p to perform the transformation:

Transformation | Source: Wikipedia

Which is reflected in these lines of code:

const xformed = q ^ circularShift(q, 1) ^ circularShift(q, 2) ^ circularShift(q, 3) ^ circularShift(q, 4);

sBox[p] = xformed ^ 0x63;

It is a good time to also acquire values for the inverse SBoxes:

// inverse sbox

inverseSBox[sBox[p]] = p;

We want to repeat this calculation for all values possible in the field, and we know that we’ve completed once our p returns to 1 - this is possible thanks to the irreducible polynomial, which we performed an indirect modulo with by XORing 0x1B.

To end off, we set the 0 values of both SBoxes; we can’t calculate these, because there is no multiplicative inverse of 0. (In other words, there is no q where 0 * q == 1)

} while (p != 1);

sBox[0] = 0x63;

inverseSBox[0x63] = 0x00;

The complete code for SBox can be found through this link.

Step 2: Key Expansion

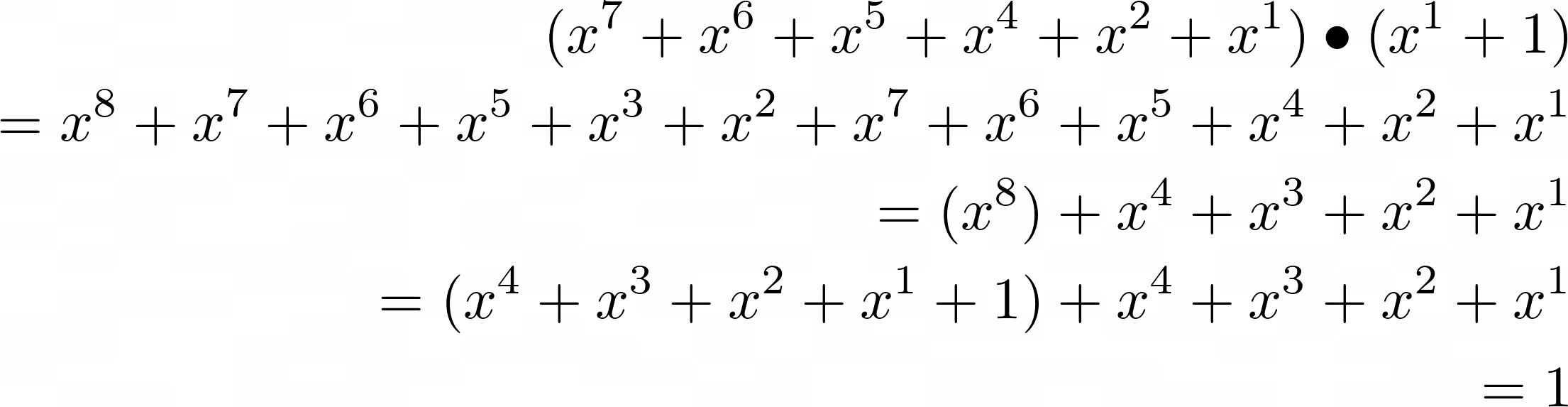

Don’t worry, it only gets easier (to understand) from here on out. In fact, all we need to do now is to follow the definitions stated on the AES Key Schedule Wikipedia Page.

Here is a screenshot if you don’t want to click a link:

Key Schedule | Source: Wikipedia

So we copy the round constants (this is trivial to implement, so I didn’t bother and used a table instead):

const roundConstants = [ 0x01, 0x02, 0x04, 0x08, 0x10, 0x20, 0x40, 0x80, 0x1B, 0x36 ];

Then we write code for rotate word:

function rotWord(b1, b2, b3, b4) {

return [b4, b1, b2, b3];

}

and sub word:

function subWord(b1, b2, b3, b4) {

return [ sBox[b1], sBox[b2], sBox[b3], sBox[b4] ];

}

We also need to break up words into array of bytes, and vice-versa whenever we need to. So we define some helper functions:

function breakupWord(b) {

return [ b >>> 24, (b >>> 16) & 0x00FF, (b >>> 8) & 0x0000FF, b & 0x000000FF ];

}

function combineWord(b1, b2, b3, b4) {

return b1 << 24 | b2 << 16 | b3 << 8 | b4;

}

Then, we convert the Wikipedia definition of W[i] into a function:

function keyExpansionInner(k1, k2, k3, k4, i) {

if (i >= 4 && i % 4 === 0) {

const rotatedWord = rotWord(k1, k2, k3, k4);

const subbedWord = subWord(rotatedWord[0], rotatedWord[1], rotatedWord[2], rotatedWord[3]);

return keyExpansionInner(k1, k2, k3, k4, i - 4) ^ combineWord(subbedWord[0], subbedWord[1], subbedWord[2], subbedWord[3]) ^ roundConstants[roundNo++];

} else {

return keyExpansionInner(k1, k2, k3, k4, i - 4) ^ keyExpansionInner(k1, k2, k3, k4, i - 1);

}

}

Since we are implementing AES-128, our N is 4, which means that we don’t need to implement the if/else that requires N to be greater than 6. Also, I will be writing extra code to inject the first 4 words of the round key, so we can skip writing code to check if i < N.

Ideally, we want our keyExpansion function to just accept 4 words, and generate the whole chunk of round keys without any intervention. Furthermore, since the function is recursive, we don’t want to generate the same round keys over and over; so we introduce a cache.

function keyExpansion(k1, k2, k3, k4) {

// Technically, I can re-write the key expansion such that we don't need so many iterations

// in the inner function. However, this method is clearer, probably, maybe.

const cache = (new Array(4 * 11)).fill(null);

let roundNo = 0; // the round number, which increases every 4 words

// fill cache with first 16 bytes from the key

cache[0] = k1;

cache[1] = k2;

cache[2] = k3;

cache[3] = k4;

function keyExpansionInner(k1, k2, k3, k4, i) {

if (cache[i] !== null) {

return cache[i];

}

if (i >= 4 && i % 4 === 0) {

const rotatedWord = rotWord(k1, k2, k3, k4);

const subbedWord = subWord(rotatedWord[0], rotatedWord[1], rotatedWord[2], rotatedWord[3]);

return keyExpansionInner(k1, k2, k3, k4, i - 4) ^ combineWord(subbedWord[0], subbedWord[1], subbedWord[2], subbedWord[3]) ^ roundConstants[roundNo++];

} else {

return keyExpansionInner(k1, k2, k3, k4, i - 4) ^ keyExpansionInner(k1, k2, k3, k4, i - 1);

}

}

for (let i = 4; i < 4 * 11; i++) {

const previousKey = breakupWord(cache[i - 1]);

cache[i] = keyExpansionInner(previousKey[0], previousKey[1], previousKey[2], previousKey[3], i);

}

return cache;

}

And that’s our key expansion function!

Step 3: AddRoundKey, SubBytes, ShiftRows, MixColumns

These are quite simple to implement.

Firstly, adding round key. It’s essentially XORing the state with the round key. The function to do so is dead simple:

function addRoundKey(roundKeys, state, roundNo) {

const k1 = roundKeys[roundNo * 4];

const k2 = roundKeys[roundNo * 4 + 1];

const k3 = roundKeys[roundNo * 4 + 2];

const k4 = roundKeys[roundNo * 4 + 3];

const s1 = state[0];

const s2 = state[1];

const s3 = state[2];

const s4 = state[3];

return [k1 ^ s1, k2 ^ s2, k3 ^ s3, k4 ^ s4];

}

Then, we substitute bytes with the SBox. Again, this is dead simple:

function subBytes(state) {

const a1 = breakupWord(state[0]);

const a2 = breakupWord(state[1]);

const a3 = breakupWord(state[2]);

const a4 = breakupWord(state[3]);

const b1 = combineWord(...subWord(a1[0], a1[1], a1[2], a1[3]));

const b2 = combineWord(...subWord(a2[0], a2[1], a2[2], a2[3]));

const b3 = combineWord(...subWord(a3[0], a3[1], a3[2], a3[3]));

const b4 = combineWord(...subWord(a4[0], a4[1], a4[2], a4[3]));

return [b1, b2, b3, b4];

}

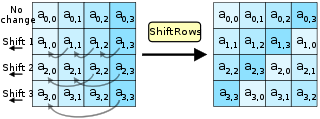

Then, we shift the rows. This image from Wikipedia shows how the rows should be shifted:

Shifting Rows | Source: Wikipedia

Essentially, we don’t shift the first row, we shift the second row by 1 byte, we shift the third row by 2 bytes, and we shift the fourth row by 3 bytes. The code to to do this is:

function shiftRows(state) {

const a1 = breakupWord(state[0]);

const a2 = breakupWord(state[1]);

const a3 = breakupWord(state[2]);

const a4 = breakupWord(state[3]);

const s1 = combineWord(a4[0], a3[1], a2[2], a1[3]);

const s2 = combineWord(a1[0], a4[1], a3[2], a2[3]);

const s3 = combineWord(a2[0], a1[1], a4[2], a3[3]);

const s4 = combineWord(a3[0], a2[1], a1[2], a4[3]);

return [s1, s2, s3, s4];

}

Next, we mix the columns; this is a linear transformation, and provides diffusion in the cipher. In essence, we’re multiplying each column, which is treated as a polynomial with co-efficients in the finite field  , with:

, with:

The fixed polynomial to multiply with | Source: Wikipedia

And then we modulo the result with:

The fixed polynomial to modulo with | Source: Wikipedia

On further calculation as denoted in the relevant Wikipedia article, the final calculation can be denoted as a matrix calculation:

The equivalent matrix multiplication | Source: Wikipedia

Which means that we can finally convert it into code. First, we need a generic way to perform XOR multiplication:

// xor no carry multiply

function multiply(a, b) {

let p = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 8; i++) {

if (b & 1 !== 0) {

p ^= a;

}

const exceed = a & 0x80;

a <<= 1;

if (exceed) {

a ^= 0x1B;

a %= 2**8;

}

b >>= 1;

}

return p;

}

Then, I figure out the code to mix one column:

function innerMixColumns(a1, a2, a3, a4) {

const b1 = multiply(a4, 2) ^ multiply(a3, 3) ^ a2 ^ a1;

const b2 = a4 ^ multiply(a3, 2) ^ multiply(a2, 3) ^ a1;

const b3 = a4 ^ a3 ^ multiply(a2, 2) ^ multiply(a1, 3);

const b4 = multiply(a4, 3) ^ a3 ^ a2 ^ multiply(a1, 2);

return [b4, b3, b2, b1];

}

Then, I wrap it up with a function that will feed each column into the innerMixColumns function:

function mixColumns(state) {

const buffer = new Array(4);

function innerMixColumns(a1, a2, a3, a4) {

const b1 = multiply(a4, 2) ^ multiply(a3, 3) ^ a2 ^ a1;

const b2 = a4 ^ multiply(a3, 2) ^ multiply(a2, 3) ^ a1;

const b3 = a4 ^ a3 ^ multiply(a2, 2) ^ multiply(a1, 3);

const b4 = multiply(a4, 3) ^ a3 ^ a2 ^ multiply(a1, 2);

return [b4, b3, b2, b1];

}

for (let i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

const brokenWord = breakupWord(state[i]);

const mixedWord = innerMixColumns(brokenWord[0], brokenWord[1], brokenWord[2], brokenWord[3]);

buffer[i] = combineWord(mixedWord[0], mixedWord[1], mixedWord[2], mixedWord[3]);

}

return buffer;

}

Done!

Step 4: Putting it all together

From Wikipedia, the outline of the steps are detailed as follows:

High level algorithm steps | Source: Wikipedia

With all of our components in Step 3, piecing them together is a matter of converting English to JavaScript:

function aesEncrypt(m1, m2, m3, m4, k1, k2, k3, k4) {

const roundKeys = keyExpansion(k1, k2, k3, k4);

let state = [m1, m2, m3, m4];

state = addRoundKey(roundKeys, state, 0);

for (let i = 0; i < 9; i++) {

state = addRoundKey(roundKeys, mixColumns(shiftRows(subBytes(state))), i + 1);

}

state = addRoundKey(roundKeys, shiftRows(subBytes(state)), 10);

return state;

}

And… done!

That’s AES encryption!

Decryption is the exact opposite process. Those steps that required mathematics will simply require inverses that are available in the same Wikipedia pages. If you would like to reference the code used for both encryption and decryption, it is available in through my GitHub repository.

MD5

MD5 is one of the hash functions that is no longer recommended by the community for the purposes of cryptography. However, it is still a cool message digest function that dominated the internet for a while; at one point, your passwords were hashed with MD5!

I have implemented MD5 quite faithfully to the pseudo-code available on Wikipedia; there really isn’t much to explain, nor any magical mathematics behind understanding the implementation. The story changes for analysis, although that is out of scope for this blog post (and my brain).

My implementation is available through my GitHub repository. Take care of endianness when representing words in any form other than decimal.

Conclusion

This was a really difficult blog post to make; in total, there are 30 images in this one post! There are some general lessons I learned from implementing cryptography algorithms:

- Endianness is hard;

- Debugging crypto algorithms is hard (searching for step-by-step test vectors is really difficult!);

- Math is hard;

- Byte rotation is the opposite of byte order direction;

- Never roll your own crypto.

There are many kinks, performance issues and probably implementation mistakes that exists in my implementation. However, this was quite a fun learning experience for me, and I hope that this blog post managed to distill the most valuable insights I gathered whilst implementing these algorithms.

Encryption and hashes are everywhere, and works beneath the hood most of the time; sometimes, it might be good to take a screwdriver, and start poking around to see what’s really going on, and how everything works. Who knows, perhaps one day, we’ll create a more powerful algorithm (press ‘x’ to doubt) to drive the world’s encryption needs.

Merry Chirstmas, and Happy New Year!

Happy Coding

CodingIndex